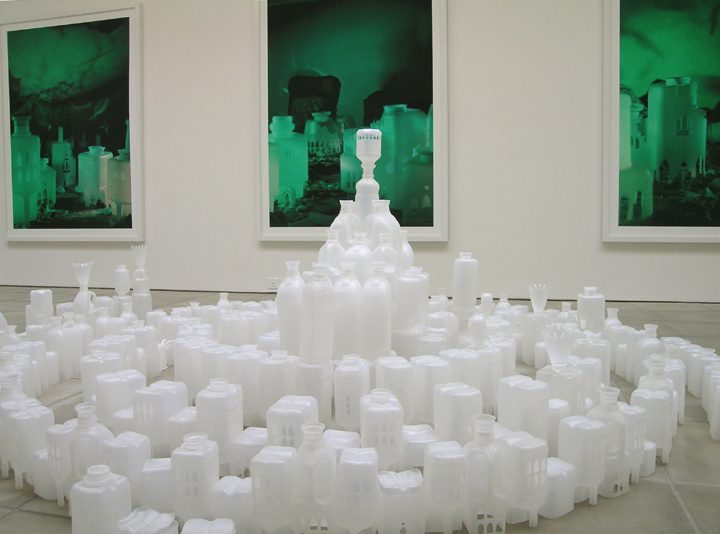

Atlantis, The Grand Tour (2009)

C-type photographic prints, sculptures, dimensions variable.

ArtSway

Hampshire

Photographs

‘Atlantis I’, ‘Atlantis II’, ‘Atlantis III’, ‘Atlantis IV’, ‘Atlantis V’. ‘Atlantis VI’. ‘Atlantis VII’

Seven 153 x 204cm c-type photographic prints

'Atlantis' was part of 'The Grand Tour', a 3 year Arts Council England funded Touring Exhibition, in which Gayle Chong Kwan explored sites of the historical grand tour, in England, France, and Italy, and developments in tourism in terms of waste, ruin, ecologies, and the senses, in particular in Dubai.

The sculptural work is a sort of perfect version of ‘Atlantis’, taken from descriptions by Plato, as well as contemporary musings many of them on the internet, about what the lost city, whose beauty was unequalled but which vanished in a day, would have looked like. Created out of used semi-transparent plastic food containers - an underwater destroyed version of the city unfolds in the large photographic works which surround it, echoing the plastic waste which collects as vast rubbish islands, in our seas and oceans.

'Gayle Chong Kwan 'Sensorial Universe'' by Sergio Giusti (excerpt) Made up of food, leftovers and waste, the universe in images by Gayle Chong Kwan is a dialectic universe. It is aware of fictional contemporary mechanisms and the flowering of latter day myths. At the same time it is aware that each mythological form - even the most marketed and marketable - requires the support of ancestral insistences, appealing in this manner to profound common structures, which function underground in silence. The mythological constructions of Chong Kwan are sensorial in nature because they are saturated in mythical thought. Thought, as Claude Lèvy-Strauss wrote, that is drawn from sensory qualities: in it the raw and the cooked are associated with the question of the binary opposition nature/culture to lead to the understanding that cooked corresponds with socialised. We could therefore say that Chong Kwan does not structure her photos, she cooks them. It is not only to underline a process of fictionalisation, but even more to highlight a cultural process and all of its implications. It demonstrates the action of culture on a basic need: food is definitely sustenance, but it is also a collector of belonging and a building block for social community. And yet, on the other side, it may also be curiosity for the exotic which is always an attempted appropriation and – in the worst cases – a touristic almost neo-colonial devouring. However the food in her exhibits does not solely denote traces of postmodernism. It is used critically and filled with the ambivalences incorporated by the food object. The construction materials for her works, in particular those for Cockaigne, are tied to the myth of the legendary land of milk and honey, and they are frequently perishable foods or waste. The land of Cockaigne does not only represent the myth of bounty, it also includes the opposing implication, the condemnation of excessive indulgence in food. That is why the processing of the food and the rite of cooking, which is primarily for conservation, is not an irreversible process here. There is an attention to the remains and to the breakdown that signs a return to the reality of shapelessness. It is a sort of backwards journey from the cooked towards incipient decay, without parading it, as Cindy Sherman does in certain works. In the series Paris Remains, the sensorial idea of Paris in ruins is explained through the utilisation of leftover food, which represents the real indelible reality of the incessant process to which the food is subjected in order to be culturalized. Something is missing: not everything may be cooked, not everything may be consumed – and assimilated. If food and leftovers constitute the building material for Chong Kwan’s works, her other guiding vector is a continuous citation that runs from Breughel all the way to the Vedutism of the Grand Tour, the educational voyage that aristocrats took from the seventeenth century forward, which constitutes the initial model for western tourism. The skies of the photographs are projected on the installation immediately bringing to mind the iconography of the views. It is once again clear that the artist is interested in the question of appropriation and its detoured implications: just as the Grand Tour tried to digest Classicism, mass tourism tries to digest the world in a more superficial and global way – pre-packaged, sweetened and adulterated for wealthy tourists. The sense of the remains is once again survival, something that may not be standardised: in the process of constructing these views, Chong Kwan continues to move from raw to cooked and back again according to a metonymical mechanism. It is as if the materials release their ancestral qualities and transfer them to the view rendering it unsettled, always ready to exude and to be corrupted – to return wild. In the case of Atlantis the double theme of mythology and food continues: Chong Kwan reconstructs the legendary submerged continent anew through metonymy. It is no longer the foods, but the containers which animate the highly imaginative scenes that once again correlate with projects that alter natural landscapes for tourism, such as hypermodern resorts like Hydropolis the underwater hotel being built in Dubai, which is one extreme example. The installation of containers in the gallery links dialectically with the photos to highlight another aspect: many of the photographs could not have resisted as installations. Due to the materials with which they are made, they would in time decay. Chong Kwan’s photographic work is literally a frozen view right before the subject begins to decompose. Once again we find a metaphor for food conservation used in an ambiguous manner. On one side a photo may be conserved, on the other it is a reminder that all conservation is an alteration, since food, inasmuch as it is matter, tends to return to its natural state and to finally decompose. That is another reason why in these photos, the foods have been conserved just a moment before they went bad: it instills a tension which stems from the purely visual and leads to the sensorial in a wider sense. It is as if by looking at the foods ready to spoil, we could already smell the odour and feel the unpleasant consistency. Even in her most recent work Senscape Scotland, the relationship with the senses remains a central theme. Food is still present, but it becomes only one of the ingredients. The Scottish scenes are in fact constructed with other objects including photographs and materials found while travelling to Scotland. The models that inspired it are the scenes that Daguerre prepared to recreate the Scottish beauties used for of light, which may be considered as a sort of virtual experience precursor. If we add that Daguerre, the official inventor of photography, prepared these dioramas without ever having visited Scotland, it becomes clear why it appealed to the contemporary sensitivity of Gayle Chong Kwan. It is again the ambiguous relationship between reality and photography, the first media copiers of reality, which however create doubles, mirrored images – they are already virtual images. However, Chong Kwan did not stop at the problem of virtual simulation here either: the title refers to the senses and the senses are not only visual. Her reconstructions are highly ritual and aware of the sensorial qualities of the materials as well as the mythological thought of the Amazonian people studied by Lévy-Strauss – connected to reality much more than is commonly believed.